According to the proto-gospel of St. James, Joachim and Anna are the grandparents of Jesus. Their daughter Mary was born late in life, a long-anticipated gift like the child of Abraham and Sarah or Elizabeth and Zechariah.

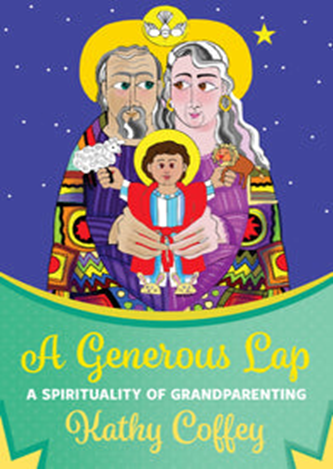

My most vivid image of the couple, understandably, appears on the cover of my book, A Generous Lap: A Spirituality of Grandparenting. With understated humor, artist Micky McGrath gave Anna big hoop earrings and both grandparents are cloaked in vivid symbols of mountains, sun and stars. Held in that cosmic embrace, the child Jesus endearingly wears bunny slippers to symbolize his resurrection, and holds tiny stuffies in his hands, the lion and lamb, of Isaiah 11:6. The title of the art, “Jesus Has a Sleepover with his Grandparents” places today’s tired, bewildered grandparents in a long and sacred line.

Anna and Joachim must’ve been puzzled when their daughter told them the strange circumstances of their grandchild’s birth. And Joseph’s parents must’ve looked for their son’s resemblance in the mysterious child. In short: confusion is OK, maybe even holy.

When Pope Francis established a World Day for Grandparents and the Elderly, celebrated on the Sunday closest to this feast, he must have been remembering his own Nonna Rosa. Rosa, her husband, and her son Mario had emigrated from Turin, Italy to Buenos Aires in 1929, fleeing poverty. Although it was high summer in the southern hemisphere, she wore her fox-collared coat for the journey because she had sewn in the lining the money from selling their family home.

Many consider Nonna Rosa the most important woman in Pope Francis’ life. Rosa lived around the corner from his childhood home in Buenos Aires, and looked after little Jorge as his four younger siblings were born. She continued to play an influential role until she died in his arms in 1970, when the future pope was thirty-four. When Cardinal Bergoglio moved to Italy to become Pope Francis, it brought his family history full circle. In many ways, Italian language, food, and customs must’ve felt familiar. His Nonna Rosa had prepared him long before for a life no one could have predicted. So too, grandparents have no idea what the century ahead holds for their grands—but they give them a firm foundation in love, a launching pad in care that can carry them far.

Let’s give the pope the final word here: “Grandparents are a treasure. Often old age isn’t pretty, right? There is sickness and all that, but the wisdom our grandparents have is something we must welcome as an inheritance.” And: “One of the most beautiful things… in the family, in our lives, is caressing a child and letting yourself be caressed by a grandfather or a grandmother.”[1]

Excerpts from A Generous Lap: A Spirituality of Grandparenting. Orbis Books, 800-258-5838, or website: https://orbisbooks.com/

[1] https://www.osvnews.com/amp/2021/07/08/pope-francis-offers-tip-of-the-zucchetto-to-grandparents-and-the-elderly/